Testing in Nepal

It's been quite some time since I last gave an update on FreePulse, but for a good reason: I've been working around the clock to prepare for the first round of in-hospital tests in Nepal!

What We've Done So Far

The GoFundMe for FreePulse received a humbling and overwhelming response this summer, raising $1000 more than the projected goal. This generosity allowed me to push forward prototyping the fully functional model of FreePulse, which led to steady improvements in the design as well as a steady increase in the amount of wires sprawled out across my desk.

There were four major areas of improvement that version 1 of FreePulse entailed, so I'll give a quick overview of the work that was done over the latter part of 2016. Each of these topics could be a blog post in their own right, and I aim to expand on them in more detail in the future.

Improvements to the Software

The software of FreePulse was completely revamped during the summer to use a new modular, sandbox-like approach to displaying graphical elements like signal traces and buttons. You can check out much of the progress on that front in this PR (and on that note, you can always be up-to-date on the latest software progress by checking out the FreePulse GitHub page!). More work is still to be done here, but these modifications have laid the groundwork for expanding FreePulse's capabilities to display many different kinds of modules and signals.

Addition of Pulse Oximetery

Using a sophisticated and efficient analog front-end chip from TI, a low-cost and hardware-efficient pulse oximeter module was added to FreePulse. This module accepts a standard DB-9 port probe, meaning it is compatible with a wide array of existing pulse oximeter clips.

The software algorithms for calculating percent oxygen content are all available on the GitHub page. These algorithms were determined empirically by testing against gold-standard reference pulse oximeters and fine-tuning calibration parameters.

Addition of Semi-Automatic Blood Pressure Measurement

Using a standard connection hose that will fit virtually any existing blood pressure cuff, the non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP) unit was built to provide simple blood pressure measurements at minimal cost and complexity. I added a DC control valve and pressure sensor to control the release and detection of pressure fluctuations in the cuff, and the extraction of pulse rate and blood pressure were performed in software. What this means for the user is that in order to take someone's blood pressure, you simply have to hit "Start" and pump the cuff up to 200 mmHg with a hand pump. After the cuff is inflated, the deflation and pressure detection is completely automated, making it a very hands-off procedure.

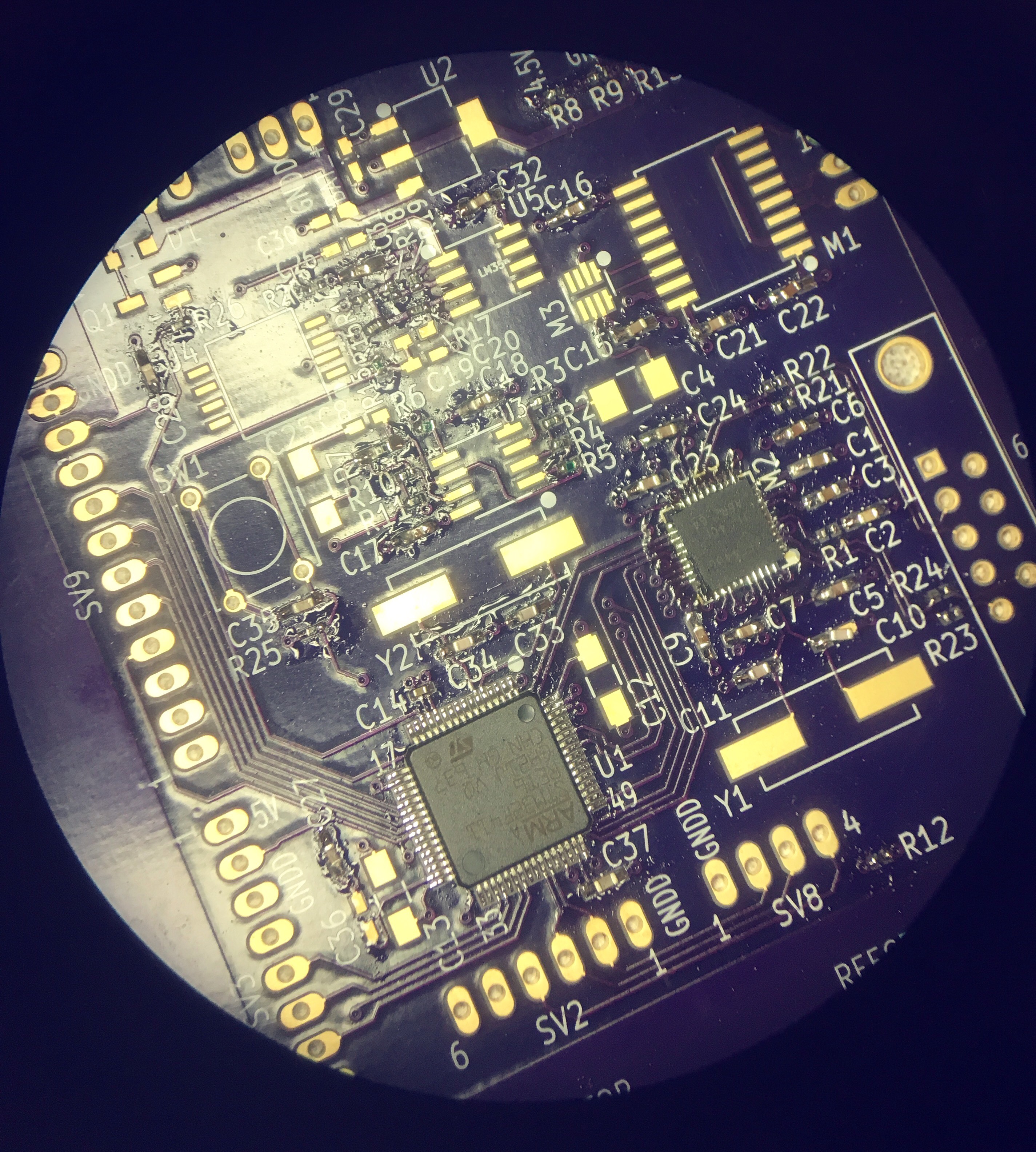

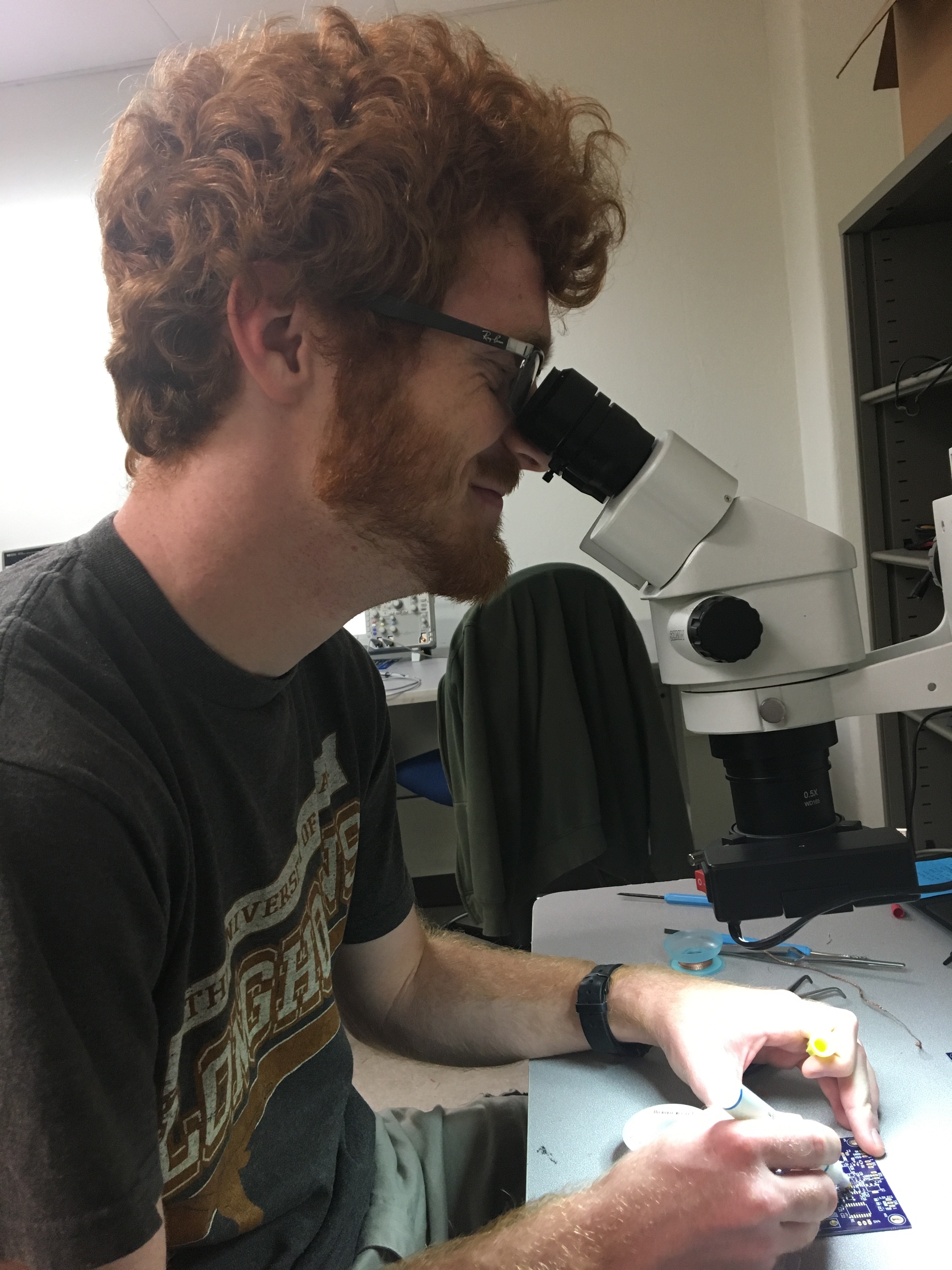

Development of a Printed Circuit Board

After spending so much time with this mess of wires on my desk, it was time to translate that into a clean printed circuit board (PCB) that would be used in the prototype devices. Working with Mrs. Barbara Burcham, an incredibly talented (and patient!) PCB layout professional, we designed and revised a circuit board that saved as much space as possible while retaining full hardware functionality. I'm thrilled with the result, and the biggest testament to Mrs. Burcham's talent is that the fully assembled board was able to be programmed on the first print! That doesn't happen very often.

Preparing for the First Hospital Test

While improving the technical aspects of FreePulse, I also began working with contacts in Nepal to organize on-the-ground tests of FreePulse's capabilities. Two organizations played critical roles in supporting this effort: Access Health Care and Innolitics, LLC. In addition to this, an incredibly generous donation from Yujan and Mekha Shrestha was the final gift that covered the rest of the budget for the proposed test trip. With the support of these donors, the testing and evaluation was set for this coming winter.

In preparation for this opportunity, a copious amount of background research and testing was performed to ensure safety compliance and hospital readiness. I began reaching out to doctors in Nepal and gauging community interest in the project, and eventually I determined what hospitals would be optimal fits for FreePulse's first on-the-ground test. After determining the hospitals, the full weight of effort became preparing a prototype that would be functional both in its operation as well as its form factor. I needed a PCB, and I needed a case!

For the former, I used the PCB design that Mrs. Burcham and I were developing and fabricated it using OshPark, a community-driven PCB manufacturing site. I then modeled a case for the monitor in Solidworks and fabricated it using an ABS 3D printer. Although the schedule was tight, two functional FreePulse prototypes are now on the ground in Nepal!

What We're Up To Now

Videographer and media guru Madeleine Dunaway and I are on the ground beginning our visitation of the three hospitals from which we will be testing FreePulse: Amppipal Hospital, Okhaldhunga Community Hospital, and the Annapurna Neurological Institute. Our goal is to demonstrate FreePulse's efficacy and receive user feedback from doctors and nurses that will guide the development of the next iteration of FreePulse. We are thrilled at the opportunity to work with the doctors and nurses at these hospitals! We hope to build relationships that will help us to better understand what needs are experienced by medical professionals in the developing world and how we can design better medical equipment to satisfy those needs.

I will be blogging about our experience here and sharing the lessons we are learning, as well as sharing some footage of FreePulse in action in the field. Stay tuned here or at the Access Health Care blog to get the latest updates as we begin our adventure in Nepal!