An Update on FreePulse

It's been eight years since FreePulse hit the ground for testing in Nepal, and in the intervening time I have written very little about what development has been happening on the project. An update is long overdue, because this period has been anything but quiet. As may have been evidenced from my previous posts, the Nepal "pre-clinical trial" ultimately became a humbling experience where I learned how far there was still to go before FreePulse could achieve its goal of bringing affordable, high-quality diagnostic care to clinical settings around the world. In the time since then, I have been focused on refining FreePulse's design and refocusing the project on the user needs of the clinicians with whom I have had the opportunity to connect.

Retrospective on the 2016 Nepal Demo

It was clear from the 2016 demo of FreePulse in Nepal that I did not fully understand how complex some of the biomedical problems in patient monitor design could get. While the FreePulse prototype seemed to work well on the subset of test cases I had available-- primarily, myself and my family-- the range of real-world signals and environments was much more dynamic, and the design did not generalize well to them at all. As a result, the FreePulse demo did not function anywhere close to the benchmarks I had hoped to see. Not to mention we also experienced several board failures during transit, such as components breaking off the circuit board due to mechanical stress during travel.

This failure of the FreePulse prototype to operate as expected felt like a big defeat. Especially given the incredibly generous outpouring of support I had received for the FreePulse GoFundMe campaign, and the individuals who had given so generously to enable this trip, it felt like I had let everyone down. I struggled with how to summarize the trip on this blog and trashed four or five different attempts at a post.

However, there was still so much that I learned in the process of visiting these hospitals across Nepal. Not only did I get to observe how patient monitors were used in three very different hospitals-- a public district hospital, an NGO-funded hospital, and a privately funded hospital-- but I also got to build contacts and relationships with many of the medical professionals there. Even though it wasn't functioning at the level it should, the prototype still served as a useful tool for showing the intended form factor and use cases for FreePulse and getting feedback from doctors and nurses who used it. Across the board, I heard the same message: a patient monitor with these capabilities, at this price point, would dramatically improve how acute care can be administered to patients. The 2016 FreePulse demo just wasn't that device.

Bridging the Gap: My Professional Experiences at Innolitics

Some lessons are best taught by experience. In the case of FreePulse, many of the lessons I needed to learn about what makes a successful medical device came from getting to work on a bunch of different medical devices in my professional career. In parallel with my work on FreePulse, I am working as the director of engineering at Innolitics-- providing engineering and consulting services to clients from all over the medical device space. This has been a fantastic opportunity to learn from sharp minds all over the medical industry, see many different kinds of medical device projects, and hone both my technical and project management skills. It's also been a privilege to do so alongside David Giese and Yujan Shrestha, the two co-founders of Innolitics who have been mentors to me and also early supporters of FreePulse-- including the Nepal demo.

As I've worked with lots of different medical device companies, I've observed that the ones that succeed and really make an impact are those that focus on the users first, and derive their solution from there. In contrast to starting with an idea for a device or technology, it is important to start with a problem and work with clinical experts along the way to make sure you solve it in a way that is safe, effective, and useful. The user needs must inform the technology.

An example: a medical device was designed which took a patient's CT scan from a month ago and aligned it spatially with a CT scan from today. Engineering spent months of effort increasing the alignment accuracy from 80% to 99%. However, it turns out radiologists only needed the alignment to be a first best-guess to get them close to the right location, and they could quickly scroll to adjust the position within the scan. Thus, the months of effort were wasted, as 80% was more than sufficient for what the user needed.

Needing to focus on users first may seem obvious. However, as the complexity of a project grows, and the further engineers are separated from the actual end-users of the application, the higher the risk that the solution diverges from what the user actually requires. Given the scope and scale of many medical device projects, this frequently becomes a huge (and very expensive) problem!

When reflecting on FreePulse's development, I realized I had started the project with a solution already in mind. I think this is an easy thing to do, particularly when there are similar existing devices on the market. Originally, the idea was for FreePulse to be "like existing patient monitors, but more affordable." However, that short-circuits the process of discovering user needs. I needed to talk with clinicians to discover what problems they experience and identify how they are not being met with existing solutions. FreePulse wouldn't be helpful if it just repeated the same pattern of existing solutions-- it needs to solve a different collection of clinical problems, those unique to low-resource environments.

In an effort to drill down to what these needs are, I assembled a survey that I sent out to the doctors and nurses after I returned home. In this survey, I asked questions about how existing patient monitors were used, but also ways in which technology needs were not currently adequately being met. The responses from this survey helped form the basis of the user needs I now have for FreePulse.

One response from Dr. Erik Bohler at Okhaldhunga felt like an appropriate summary of the key need that FreePulse is trying to solve:

Sometimes we have too few nurses to be able to watch the critically ill patients continuously. More and better monitors will not solve that problem, but could help our nurses use the time they have more effectively.

Patient monitors don't themselves save lives-- however, they can help hospital staff to save more lives by using their limited resources more efficiently.

Technical Progress

After refining my collection of user needs and distilling those down to requirements, I began the work of designing and building the next version of FreePulse. Over these past several years, I've completed several technical milestones:

- I've re-written the firmware of FreePulse in Rust, a memory-safe systems programming language (you can read more about this in my previous post on the subject)

- I expanded the ECG module to support 12-lead ECG and implemented proper medical-grade (e.g., IEC 60601-1) electrical isolation

- I refined the pulse oximetery (SpO2) calculation algorithm and implemented a semi-automated probe calibration system using an on-board spectrometer

- I implemented a new non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP) measurement system with an integrated pump (no more manually inflating the cuff)

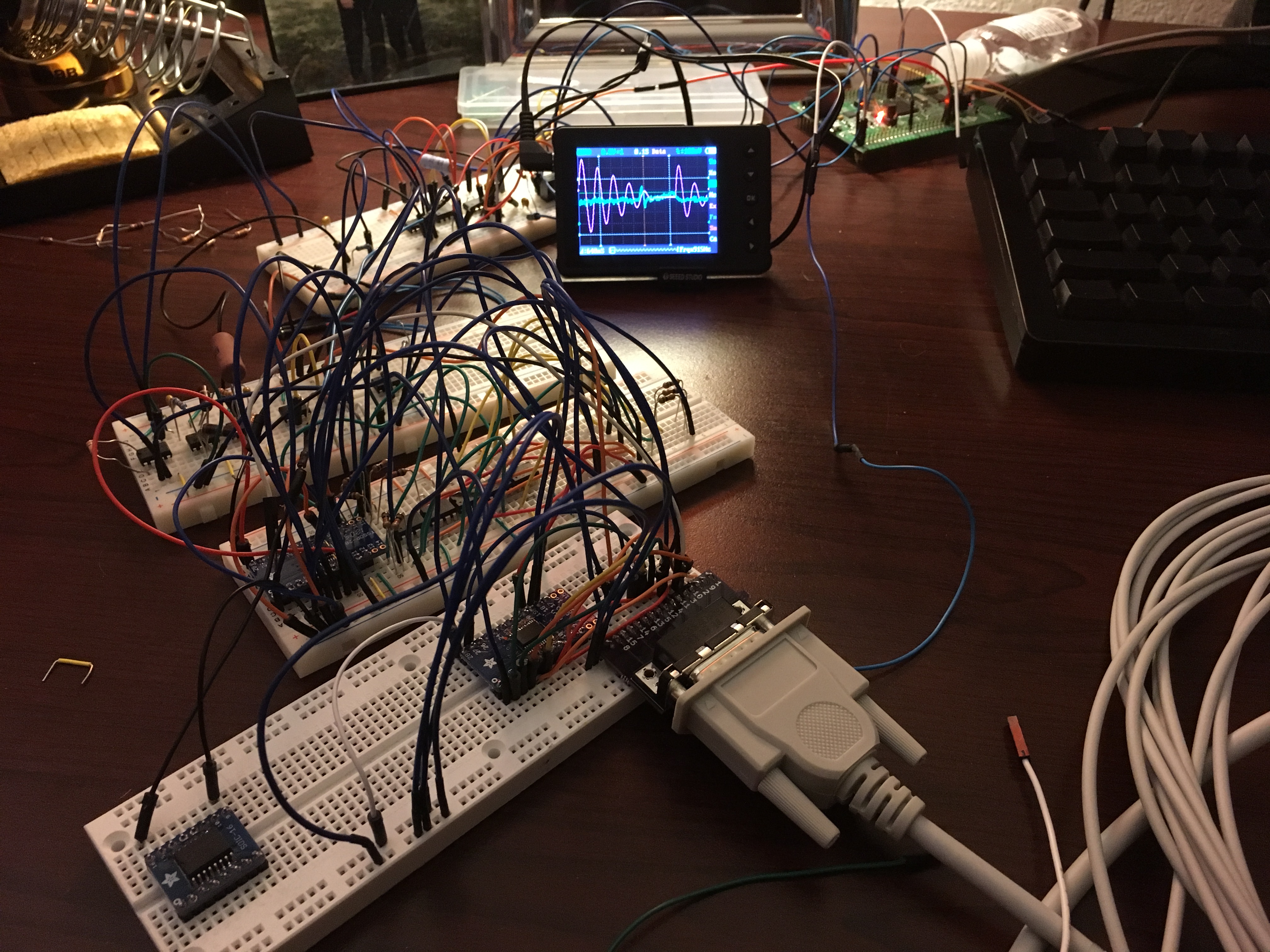

The 12-lead ECG system built out on a breadboard. A rat's nest of wires!

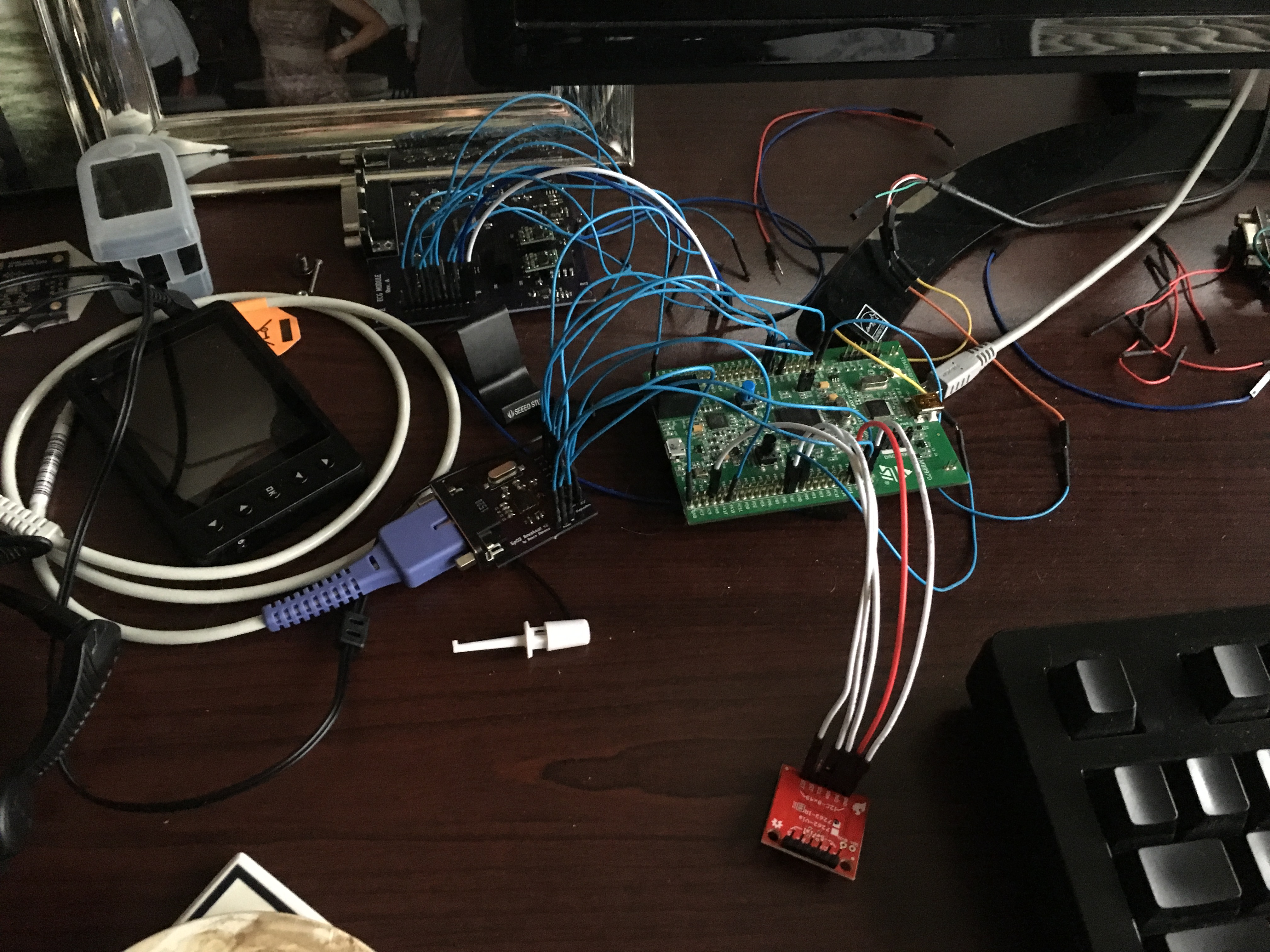

FreePulse after moving the 12-lead ECG system and the SpO2 system to dedicated PCBs

I will dive more into each of these milestones in a separate blog post, since there's a lot to be said on each of these topics! Suffice it to say for now, this was a huge undertaking and I am proud of the progress made so far. There's still a ways yet to go, though:

- Implementing and verifying the NIBP calculation algorithm (a surprisingly complex task)

- verifying the pulse oximetery algorithm and calibration system

- verifying the ECG system

- Finalizing the user interface

- Implementing alarms, battery management, and logging

You'll note that verification of the critical functions of the monitor are some of

the biggest remaining tasks. Verification has proven to be a challenge because

testing equipment for patient monitors is extremely expensive. If you or

someone you know is in a position to lend access to a patient monitor simulator

tool such as the Fluke ProSim 4 or the ProSim SPOT

Light, please do reach out to me at reece@freepulsemed.com! It

would be an enormous help!

WHO and Next Steps

As the technical pieces of FreePulse are coming together, I also have been looking for opportunities to get more input on the design and raise awareness for the project. I submitted FreePulse to the 2022 WHO Compendium of innovative technologies for low-resource settings, which was a wonderful opportunity to discuss the design of FreePulse with a panel of talented scientists and engineers with a unique perspective on the kind of medical devices that can succeed in low-resource environments. While FreePulse was too early-stage to be included in the publication, I did receive invaluable feedback from the reviewers. In particular, they emphasized that building a patient monitor that can be sold at the specified price point of $300 USD or less would help meet an exceptional need at a highly competitive price point.

With clear signals that the design is heading in the right direction, I am now focused on finalizing the hardware design and beginning the algorithm validation process. Once I've been able to test the system against a wide range of simulated input signals, I will then begin finalizing design documentation and planning for the next big step-- a clinical trial evaluating FreePulse's effectiveness.

Personal Update

FreePulse hasn't been the only thing changing since the Nepal Demo in 2016. At that time, my then-fiancé Madeleine and I were travelling together trying to get FreePulse off the ground. In the intervening time, we've gotten married, bought a home, survived a pandemic, and had two amazing kids. Life doesn't slow down for a second! Our experiences travelling together and meeting all these incredible people have been a powerful foundational experience for our family.

Conclusion

FreePulse has come a long way in eight years, and I am excited for the next steps to see this project grow. I went far too long without providing updates on the project-- I will do my best to keep this blog updated and "learn in public" as I continue development and begin down the road of verification and validation testing.

If you're interested in helping, there are two key areas I could use help with right now:

-

Do you have clinical experience as a doctor or nurse? If so, please consider filling out a user needs questionnaire!

-

If you or someone you know is in a position to lend access to a patient monitor simulator tool such as the Fluke ProSim 4 or the ProSim SPOT Light, please do reach out to me at

reece@freepulsemed.com! It would be an enormous help!

Thank you to everyone who has followed along, encouraged me, and lent their support up to this point. I am so grateful, and I am excited to see what next steps FreePulse will take.