What's the Deal With FreePulse?

I've been working on the FreePulse patient monitor for about one and a half years now. The original project idea came about as a result of my experiences in Rwanda in the summer of 2014; since then, it has become more refined (both conceptually and technically) based on feedback from doctors, nurses, and device distributors from around the world. As the second version of the prototype is now in development, I think it's an opportune time to look back on the motivation and history of FreePulse to understand how far we've come and how far we have to go.

The Root of the Problem

In the summer of 2014, I had an incredible opportunity to work with an organization called Engineering World Health. The program they run, called the Summer Institute, trains engineering students in the maintenance and repair of medical equipment and then sends them to local hospitals in the developing world to work as biomedical technicians. After a month of training in Kigali, Rwanda, I was stationed at Kabgayi District Hospital, a local hospital for the Gitarama district.

_A health center in rural Rwanda_

_A health center in rural Rwanda_

During my time at Kabgayi, I worked closely with the medical and maintenance staff and began to be integrated into the community. The more the staff welcomed me into their daily lives, the more I was able to slowly understand the scope of the issues they dealt with on a daily basis. Doctors routinely had to take care of patients while lacking critical devices or supplies, maintenance officers had to try and fix much-needed equipment without any spare parts, and administration officials tried to procure the items that the hospital needed with a minuscule budget. The staff was hard-working, intelligent, and creative; however, they constantly had to fight against the odds to take care of their patients.

One need that was particularly pressing for the hospital was a lack of patient monitors. Patient monitors are devices that keep track of a patient's vitals signs-- their electrocardiogram (ECG), blood oxygen content (SpO2), and blood pressure (NIBP)-- and they are required any time a patient is put under anesthesia and recommended for every bed in the emergency ward. Most hospitals in developed countries have a large amount of these monitors, since any patient in a questionable state of health needs to have at least one of the above vitals signs monitored. However, at Kabgayi, there were only five. Five patient monitors for 404 beds. Surgeries had to be delayed, monitors had to be cycled between patients in the emergency ward, and sometimes monitors would have to be shifted back and forth between maternity and emergency via a long, unpaved, and uncovered path.

_The path from emergency to maternity at Kabgayi District Hospital_

_The path from emergency to maternity at Kabgayi District Hospital_

After returning back to the States, I began development on the beginnings of an idea as the design project for our university's Engineering World Health chapter: what if a patient monitor could be built at an affordable price so that hospitals could buy multiple devices from their own budget? If that could be accomplished, administrators wouldn't have to wait on donations to get new equipment, and the device could actually be optimized for developing world environments. As I began fleshing out the technical details of the monitor and building circuits, the idea became more of a reality, and the core elements of FreePulse were born.

From Paper to Prototype

After about five months of intense research, circuit design, and programming, a mock-up of the monitor was finally built with a working ECG and display. From the breadboard design, I was able to pull out testable data, which we then submitted to the Engineering World Health Design Competition and National Institute of Health (NIH) DEBUT competition. However, the project idea wasn't finished after the design proposals were submitted; I had just taken a job as a coordinator for the EWH Summer Institute, and I wanted to bring a working prototype to Rwanda with me. So, working together with Abhishek Pratapa, a fellow member of TEWH, we designed a PCB and casing for the monitor, finishing the day before my flight to Kigali.

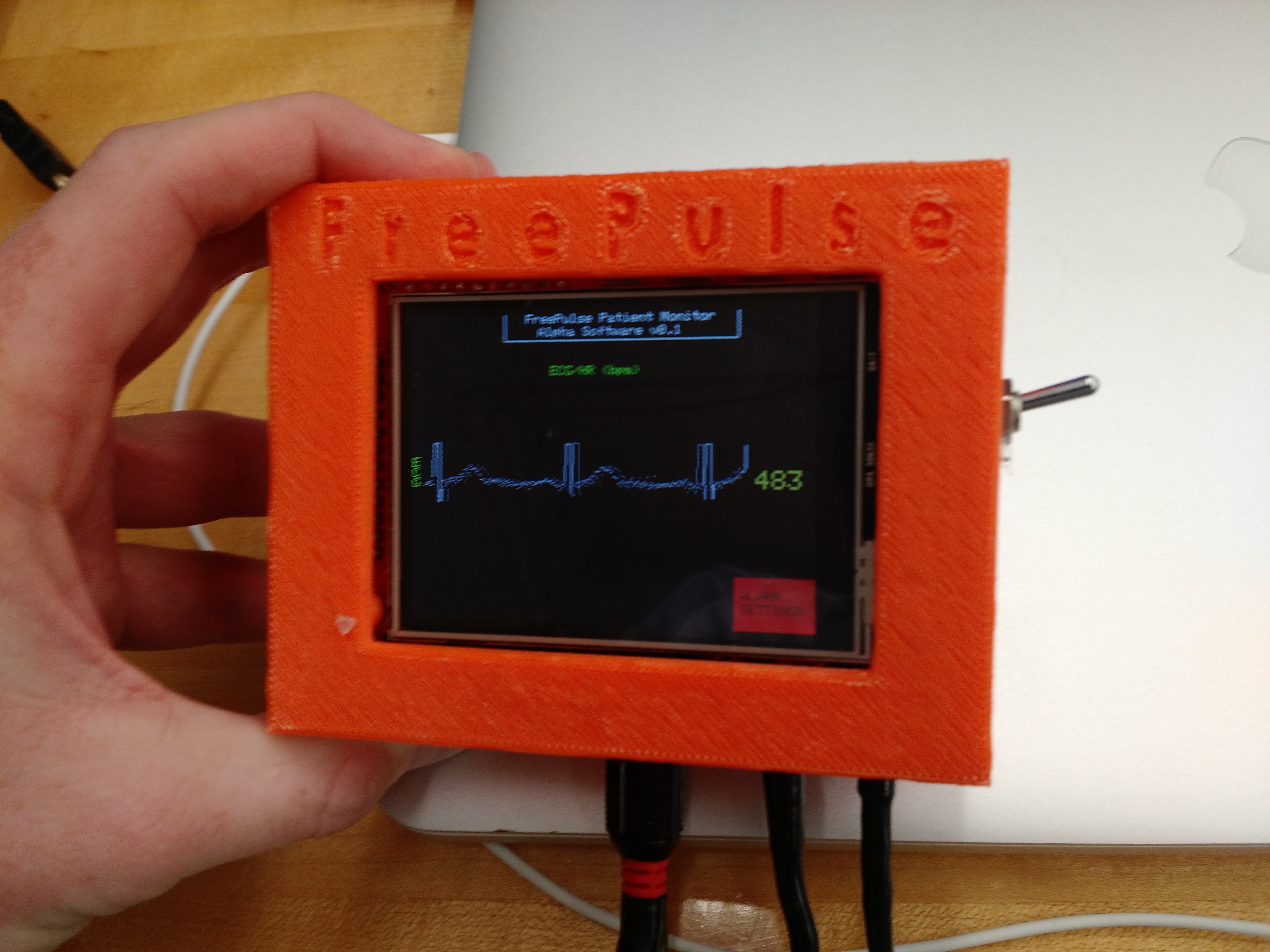

_The first-version prototype of FreePulse_

_The first-version prototype of FreePulse_

I'll take a moment here to recognize the members of TEWH who played integral roles in getting the project proposal submitted: in the research department, Courtney Koepke, Fatema Nagib, Anamika Chourisa, and Alina Schroeder all played crucial roles in collecting valuable statistics and background information for the proposal; in the business department, Akash Patel drafted a business model for our proposal that explored the ability for our project to be sold directly to developing world hospitals; and in the development department, Abhishek Pratapa and Ajay Rastogi both helped to get the prototype to a testable stage in time for the proposal. Many of these individuals are now working on new projects focused in developing world healthcare, which you can read more about at www.tewh.org.

And so, I hopped onto a plane to Kigali with the first prototype of the patient monitor. During that summer, I met with doctors and device distributors in Rwanda and began talking with them more seriously about hard numbers: what were the specifications they needed? What price points would be affordable for hospitals? How would the devices be distributed? After gathering this research and getting initial feedback on the form factor and user interface of the device, I began sketching out the ideas of the version two prototype of FreePulse.

Nepal That and a Bag of Chips

Finally, amidst the number-crunching and circuit design of the second prototype, I had a unique opportunity to travel once again with EWH, this time to Nepal. During the winter of 2015, I was stationed both in Kathmandu as well as Okhaldhunga, a rural district in eastern Nepal; while I was there, I began investigating how FreePulse would perform in these settings and interviewing doctors. The feedback I received from this trip helped to shape the final design of the second version prototype, and in the process, I was able to form connections with doctors who were excited about the idea of getting FreePulse into the field and helping to make the project a reality.

I've been extremely blessed to be able to travel as much as I have, and the fruits of that travel have been an increased network of awareness and support for FreePulse both in Rwanda and Nepal. It is my hope that the finished secondary prototype can undergo field testing in one of these countries, after which a release version of the product will be developed. For news and updates on this front, you can subscribe to my blog via RSS or follow me on Twitter-- all updates will be coming through those two channels!

_The maintenance office and canteen at Okhaldhunga Community Hospital_

_The maintenance office and canteen at Okhaldhunga Community Hospital_

Where We Are and Where We're Going

Technically speaking, what's FreePulse got? Right now, here's where the project stands:

- 3-lead ECG measurement and heart rate detection

- SpO2 measurement (in development)

- semi-automatic NIBP (in development)

- 5" color touch screen interface

- About 10 hours of battery life

- Uninterrupted switch from wall power to battery and back

- Alarm system for heart rate and SpO2 (including piezo alarm)

I'll be blogging about interesting aspects of developing FreePulse here, and if you're interested in the technical side of things, you can check out the code base. All of the software for FreePulse is open-source and available in the GitHub repository. Finally, if you have any questions or simply want to know more about the project, feel free to email me (address is at bottom of this page)!

I'm excited to see the progress FreePulse is making, and I hope you are too. I want to create something that will make a positive impact and help the many medical personnel whom I have met that have to struggle with a lack of medical equipment-- because when developing world healthcare is improved, we all stand to benefit.

_The aunt of one of my biomedical technician colleagues in Nepal, Sun_

_The aunt of one of my biomedical technician colleagues in Nepal, Sun_